Three members of VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences donate kidneys to save lives of friends, family and strangers

They share a deep sense of reward and hope others will follow to help patients in need of an organ transplant.

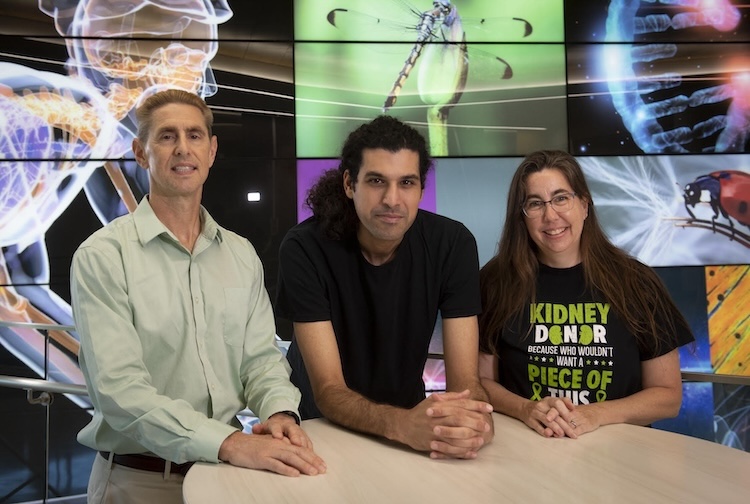

May 08, 2024 Jeff Green, Ray Ibrahim and Becky Durfee all donated their kidneys in the past year to others in need of a lifesaving organ transplant. (Enterprise Marketing and Communications)

Jeff Green, Ray Ibrahim and Becky Durfee all donated their kidneys in the past year to others in need of a lifesaving organ transplant. (Enterprise Marketing and Communications)

By Joan Tupponce

Before January, Becky Durfee, Ray Ibrahim and Jeff Green didn’t know one another, even though they all work in Virginia Commonwealth University’s College of Humanities and Sciences. Now, they share a bond — the act of saving a life through kidney donation.

In the span of seven weeks this semester — on Jan. 3 and 4 and Feb. 21 — all three donated kidneys. Each were motivated to help when another person was reaching their breaking point.

For Durfee, assistant chair in the Department of Statistical Sciences and Operations Research, the journey began in February 2023 when she saw a friend’s Facebook post.

“It said that her brother would die without a kidney transplant. I filled out the questionnaire right then and there,” Durfee said.

If you have a friend who needs a kidney, you don’t have to pray that a family member will donate because you can.

I feel amazing about what I have done.

Becky Durfee, VCU professor and living kidney donor

For patients who need a lifesaving organ, there are two options: join a waitlist and hope for a matched organ from a deceased donor or find a living donor.

As of mid-April, more than 89,000 patients are on the waiting list for a kidney, according to the Health Resources & Services Administration, an agency of the Department of Health and Human Services.

The number of people on the national waiting list far exceeds the number of organs available for transplant. Having a living donor – who is oftentimes a family member, friend or altruistic stranger – speeds up the process significantly.

The steps to become a living organ donor

The screening process to see if Durfee was a match for her friend’s brother, James Wood, took about 11 months, which included a full range of blood tests, lab work and various other tests.

At VCU Health Hume-Lee Transplant Center, where Durfee’s care was overseen, prospective donors also speak to mental health professionals to ensure they understand the donation process, the risks and to make sure they aren’t doing anything against their will.

“They made sure I was healthy enough to donate,” she said. “I spent one entire day at VCU Health being scanned from head to toe.”

On Jan. 3 this year, Durfee had a kidney removed at Hume-Lee Transplant Center through a minimally invasive robotic surgery. Hume-Lee surgeons have been doing innovative robotic procedures for kidney procurements since 2016.

“They made three one-half-inch incisions that look like birthmarks. The surgery was about 2½ hours, and I stayed in the hospital for two nights,” she said.

As soon as her kidney was removed, the medical team had it flown to Atlanta, where the recipient was waiting.

“His transplant was successful. Three days after the surgery, his kidney function levels were better than they had been in 20 years,” Durfee said.

Jeff Green and Becky Durfee shared their experiences as living organ donors with VCU students during a Donate Life Month event in April. (Enterprise Marketing and Communications)

Giving the gift of life

For Ibrahim, the donation was a way he could help his older brother receive a kidney, even though they don’t share blood types.

“My brother needed a kidney when he was young because he had kidney disease,” said Ibrahim, a graduate student in the Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics. “Luckily, my mom was able to donate her kidney. But donated kidneys don’t live forever, and my brother’s kidney is failing again.”

When Ibrahim found out he was not a match, he decided to donate his kidney to someone else, so his brother could receive a kidney from another donor in return.

Luckily, Ibrahim’s brother matched with a donor in April and is now “recovering well” after surgery.

On Jan. 4 at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York City, after a year of medical testing, Ibrahim had his kidney removed. It went to a patient in Pennsylvania, and though the process is anonymous, either the donor or recipient can send a letter to the other party.

“I received a letter from my recipient and I read it. It was heartwarming,” Ibrahim said. “The recipient told me about their family and that the kidney was doing fine and they were recovering well. It was a very sweet letter. It made me feel good. I felt happy that I could help someone.”

For Green, the kidney donation on Feb. 21 had no family or friend connection. Green, Ph.D., is a social psychologist who teaches in VCU’s Department of Psychology. His friend and fellow social psychologist Abigail Marsh wrote the book “The Fear Factor,” and its focus on altruistic donations made an impression on Green.

“That started me on my path. At this stage of my life, sometimes there can be greater gains in a loss and some advantages to making yourself vulnerable,” Green said. “I was thinking of something that would be meaningful for me.”

One of the courses he teaches is about the psychology of happiness, and he has done significant research on gratitude and forgiveness

“In many respects, people get a greater feeling of well-being and happiness from giving to others,” Green said. “Knowing that some discomfort on my part would possibly double or triple someone else’s life expectancy was compelling and made the decision rather easy for me.”

Green had his surgery at Hume-Lee Transplant Center, and his kidney was transported to New York Presbyterian Hospital.

“It would be profoundly meaningful to meet the person who received the kidney,” said Green, who has had a speedy recovery. “I’m privileged to be a part of this greater motivation to help somebody. If other people knew the facts, I think we would see a lot more donations, and that would save a lot of lives.”

Rewarding for recipients and organ donors

Living with one kidney doesn’t limit your life or shorten your lifespan, Green says, who finished an Olympic-distance triathlon on April 20, swimming 0.9 miles, biking 25 miles and running 6.2 miles.

“The kidney operation was irrelevant, even though it was only eight weeks before the race,” he said.

Durfee, who went on a 10-mile bike ride to celebrate the two-month anniversary of her donation, wants people to understand how easy the process was for her.

“Everybody was worried about me doing this. What if my kidney goes bad? If it does, then I go straight to the top of the recipient list because of my status as a donor,” she said. “Matching is much easier than I thought. You don’t need to be an exact match. I am type O blood, which is the universal donor.”

Durfee’s recipient is a 53-year-old Iraq War veteran.

“He sacrificed years of his life for you and me, so I felt I could sacrifice a few weeks of mine for him,” she said. “Now he is completely back to normal.”

She hopes others will feel motivated to donate a kidney.

“If you have a friend who needs a kidney, you don’t have to pray that a family member will donate because you can. I feel amazing about what I have done,” Durfee said, noting the connection she feels with her recipient. “I saw the video of him ringing the bell after doing a lap around the ward in the hospital. Watching him ring that bell was so powerful. He sent me a picture of his new grandson – who he gets to watch grow up – and that was rewarding.”

Becky Durfee donated her kidney to a childhood friend’s brother who is a veteran. (Enterprise Marketing and Communications)

.ashx)

.ashx)